Staff

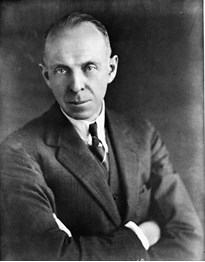

Victorian Railways Commissioner Harold Clapp was fond of repeating a comment made to him by an American railway worker: 'The railway is ninety-five per cent men and five per cent iron.' Victoria's railways have relied on the women and men who served in diverse roles to provide a state-wide transport service.

The railway system worked on a strict system of hierarchy that emphasised discipline, punctuality and organisation. Loyalty and dedication was demanded, and there was a strong expectation that workers would advance their railway-related skills outside of working hours through various training and self-improvement programs. Yet within this seemingly inflexible system there developed a strong community of workers who were passionate about the railway system. Many jobs with the railways were highly regarded, offering people secure, respected work.

When the suburban railway service merged with the bus and tram services to form the MET in 1983 this strong community underwent a difficult transition. Suburban staff were separated from country staff, with the new 'V-Line' service handling all regional rail travel. Privatisation has brought further changes, with the rail staff community being further spread across several private companies.

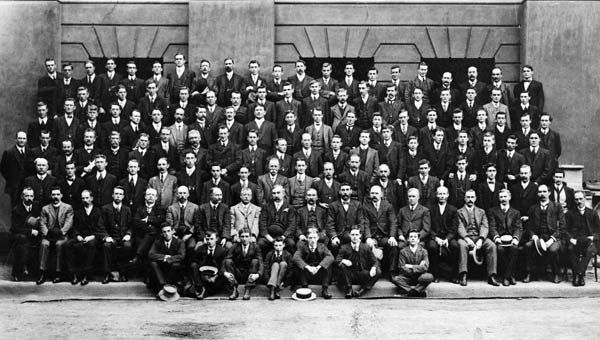

Rolling Stock Branch

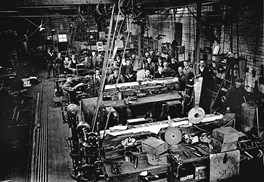

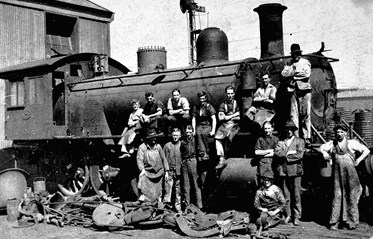

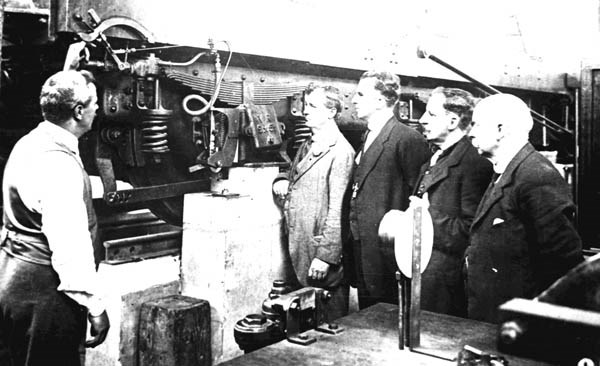

The Rolling Stock Branch focused on the design, construction, maintenance and operation of locomotives and rolling stock.

Train running crews – consisting of locomotive drivers and firemen, and later electric motormen – were the high profile members of the Rolling Stock Branch. Popular with passengers and train enthusiasts alike, the locomotive drivers occupied a coveted position, and indeed they had often spent many years working their way up through the Branch's hierarchy starting as young apprentices in the workshops. Though positions on the running crews were highly desired, they also required shift work and very long hours – both of which have at times been implicated in rail accidents.

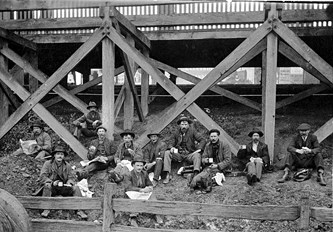

The majority of the branch's work was performed at the Newport Railway workshops, established in 1882. Additional facilities were established at North Ballarat, North Bendigo, Jolimont, Geelong, North Melbourne, Spotswood and West Melbourne. From the 1900s most of Victoria's rolling stock was produced in these government workshops. During its peak in the 1920s around 5000 workers were employed within the Newport workshop alone. Boiler-makers, upholsterers, sail makers, blacksmiths, moulders and all sorts of tradespeople worked together to build and maintain all manner of items required by the railways – from state-of-the-art locomotives to the pegs to hold the track in place.

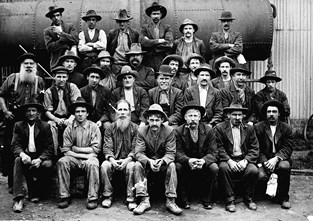

Loco crews

Workshop staff

Traffic and Commercial Branches

The Traffic and Commercial Branch has been the public face of the railways. The branch included station staff such as stationmasters, stationmistresses and station assistants (also called porters), gatekeeping and signalling staff, and on-board staff including guards and conductors. The working life of the branch's employees revolved around the train timetable and passengers needs.

Station staff performed a wide range of duties, from ticket-checking and sales to cleaning and bag-handling. Their role of assistance to the public ensured that they were amongst the best loved of railways staff. In country towns the stationmaster in particular enjoyed a respected status equivalent to that of the bank manager. As an educated government employee the stationmaster was regarded as a bureaucratic expert, and would be consulted on many matters aside from when the train was due. A strict hierarchy operated within and between stations, reinforced by the different styles of uniforms that staff of different status wore.

Conductors and guards checked that passengers held the correct ticket, behaved appropriately and were comfortable. Guards on the rural services also acted as messengers for isolated railways staff: bearing news, messages from management and railways gossip.

Whilst the trains rattled along, signalmen and gatekeepers regulated the flow of traffic through busy metropolitan railyards and remote country lines. These were positions of significant responsibility, essential to the safe-working of a system dependent on time and accurate communication.

Accommodation

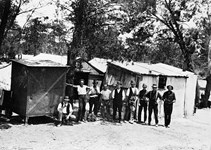

Ways and Works Branch

Ways and Works Branch staff were responsible for the maintenance of the track (the 'permanent way'). This included the regular maintenance required to keep the track and railway bridges in good working order, as well as building new sidings, crossovers and points. The replacement of earlier tracks with heavier rails capable of carrying the weighty engines and freight loads introduced post-1880 was a major task undertaken by this branch.

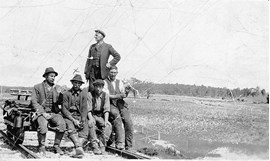

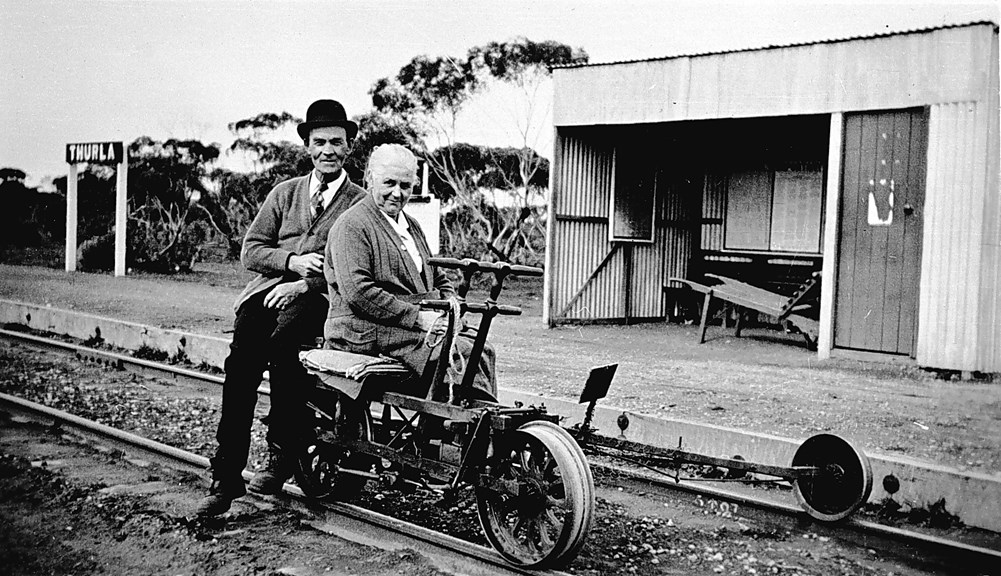

As most of the track lay outside Melbourne most Ways and Works staff were based in rural areas. Track gangs were responsible for maintenance of a particular section of track. They were required to travel the track's length daily to check for obstructions, damage or anything which could endanger train traffic. Track gangs usually consisted of a ganger and three labourers who would live in the closest local town. Their daily inspection was undertaken on gangers 'cars' or 'trolleys' – small manually powered or fuel driven vehicles which ran on the track.

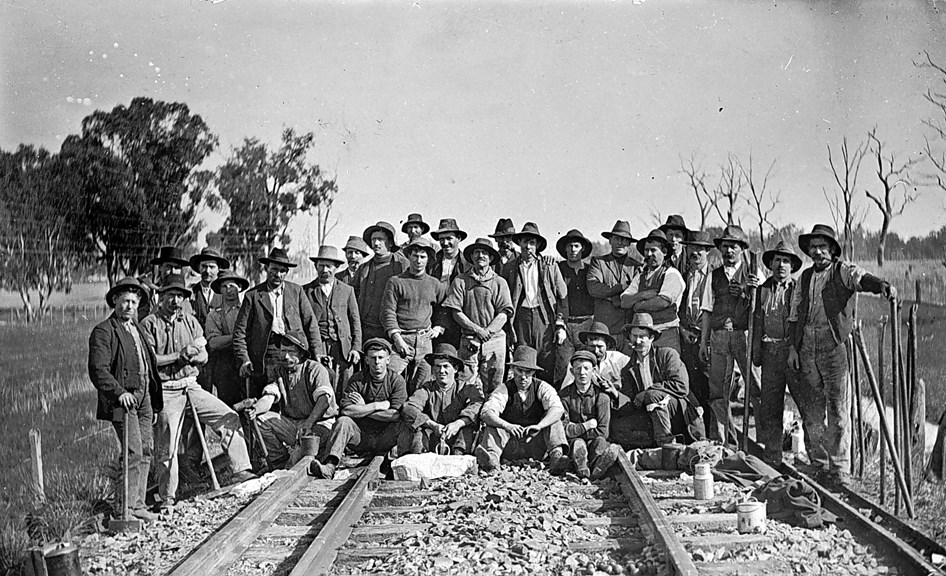

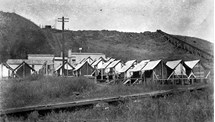

Special gangs of up to 30 staff were responsible for non-standard maintenance of the track.The work was physically demanding, and the conditions spartan. Until the 1930s they were accommodated in tents as they moved from worksite to worksite. Subsequently they were often accommodated in old railway carriages parked at country station sidings.

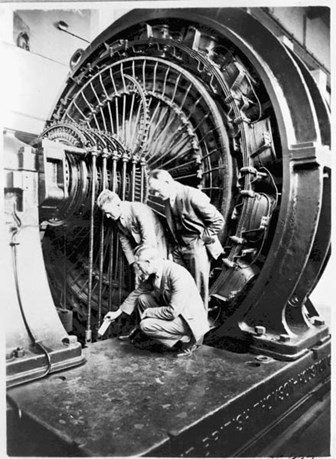

Electrical Branch

One of the smaller branches, the Electrical Branch was established to support the suburban electric trains which were officially launched in 1919. Staff members were primarily responsible for the provision and distribution of electrical power, as well as the maintenance of electrical equipment throughout the railways service.

The major responsibility of the branch was the Newport Power Station, which commenced energy supply in 1918. This station supplied power not only for Victorian Railways, but also other large metropolitan consumers. The plant was transferred to the State Electricity Commission in 1951, with a resultant decrease of staff in the Electrical Engineering Branch. After the transfer Branch staff continued to maintain and upgrade various sub-stations associated with the railway system.

The conversion of suburban carriages to electric trains was also the responsibility of the staff in this branch. Built in 1917, the Jolimont workshops were responsible both for this initial conversion and the general maintenance that this rollingstock required.

Refreshment Services Branch

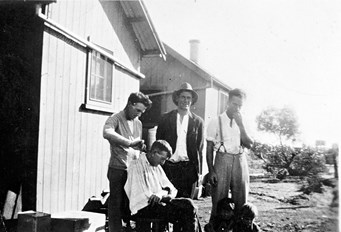

The Refreshment Services Branch was established in 1920, and initially focused on providing station-based refreshment rooms and the dining car service. Its scope expanded to include diverse activities such as stall rental; sales of advertising space on railways infrastructure; laundry services; operation of a hair-dressing salon, a bakery, a butchery and a poultry farm; and the management of the chalet guesthouse at Mt Buffalo.

The majority of staff worked in refreshment rooms and dining cars, both of which were a popular feature of the railway service. Previous to 1920 refreshment services had been provided by contractors, but after many complaints the Department decided to provide a standardised service across the system. It grew quickly: five years after it was established the Branch employed approximately 500 staff. Station refreshment facilities ranged from elaborate dining room to decorated push-carts. They were staffed predominately by women, who provided everything from a cup of tea to a three course meal.

Most refreshment room services were closed in the 1970s.

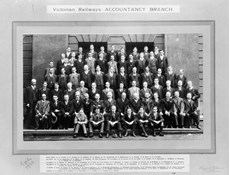

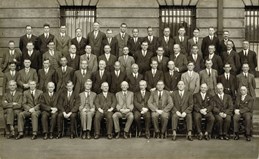

Management staff

As a major employer with staff dispersed across the state, the Department was a famously bureaucratic organisation. Whilst the Railways Commissioners were the public face of railways management, a small army of management staff were employed by the Department.

The Secretary's Branch was responsible for policy and 'high' administrative work, including the determination of employees conditions, wages and hours. The Accountancy Branch was responsible for the management of all financial matters.

Various boards and committees dealt with specific aspects of railways management. For many employees the Discipline Board was the most significant. Discipline was a strong feature of working life for railway employees. Strict codes of conduct regulated not only what tasks were to be done, but also how employees should behave whilst fulfilling their duties. Failure to abide by these rules could incur an on-the-spot fine, suspension, demotion or dismissal. Whilst senior staff could issue discipline for minor offences, the Discipline Board dealt with the serious breaches as well as hearing appeals.

Unlike all other branches, the majority of management employees were 'salaried' staff (rather than waged staff). The security and status associated with such conditions widened the division between management staff and employees of other branches.

Stores Branch

Construction Branch

There was never a construction branch as such within the Department. Some lines were built by private contractors, many were built by Board of Land and Works employees, and some were built by a combination of labour sources. Whilst many of those responsible for the design, engineering and construction of the permanent way weren't formally railways employees, they were nonetheless a critical part of the workforce that enabled Victoria's trains to run.

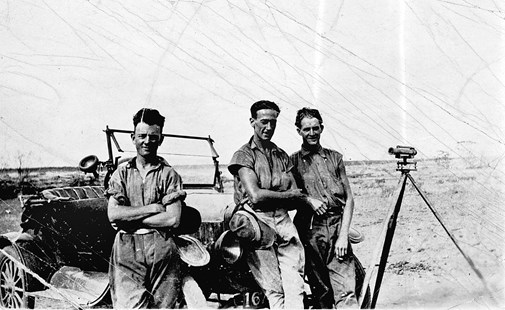

Before a track could begin, the area must be carefully surveyed. Surveyors journeyed into remote Victoria, often staying in basic accommodation and travelling for weeks at a time. Their measurements and observations were brought back to the staff engineers who would design the bridges, cuttings and curves that would enable the trains to pass through all sorts of geographical obstacles.

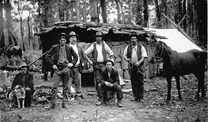

They were followed by the construction crews – the 'navvies' (labourers) and the 'gangers' (foremen). Previous to 1894 most construction and associated work was done by private contractors. Contractors were involved in all aspects of this work – from cutting the sleepers to preparing the track. Later this work was completed with 'day labour' – that is, with Victorian Railways employees rather than contractors. This was railway employment at its most physical and least resourced, and unfortunately little status or financial reward was attributed to these workers whose labour opened the lines.

Accommodation

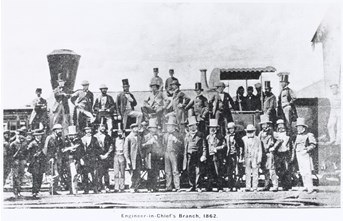

Charles Perrin, Engineer-in-Chief

Charles Heber Perrin (1867-1959) joined the Victorian Railways as a junior draftsman on 28 August 1885 and rose through the ranks as a junior engineer, site engineer and senior design engineer to eventually fill the role of Chief Engineer with Railway Construction Branch from 1923 until his retirement in 1932. During his career he was to witness one of the most remarkable periods of railway expansion in Victoria's history, during which the State's railway network grew from 2,700 to 7,725 kilometres. Amongst the many design and construction projects Charles Perrin worked on were Flinders Street Station, several Murray River bridges, the Walhalla narrow gauge railway, the Bairnsdale-Orbost and Gheringhap-Maroona Railways, South Kensington-West Footscray goods line and the Maribyrnong River Viaduct on the Albion-Broadmeadows line.

A number of the images used on this website are drawn from a magnificent bound photograph album presented to C.H. Perrin on his retirement, documenting some of the many projects he had worked on during his career.

Contractors

Surveying teams

Railway Commissioners

In 1884 an Act of Parliament appointed three Railway Commissioners to oversee Victoria's railways. Established in response to the somewhat haphazard management of early railways, the Railways Commissioners' authority encompassed management, construction and maintenance of the railways.

Initially the Commissioners' powers were far-reaching and relatively unchecked. This was altered in 1892 when authority over railways construction was returned to the Board of Land and Works, and Commissioners were required to work more closely with other management personnel. These changes were followed by a period of turmoil in management. By 1896 the number of Commissioners had been formally decreased to one. The practise of appointing three Commissioners was reinstated in 1903 and persisted until 1973, when their function was replaced by the VicRail Board.

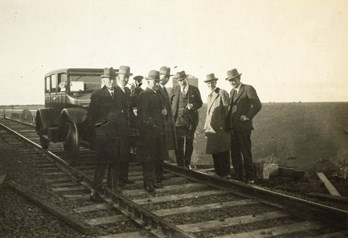

For all their influence over the lives of railway workers, the only contact many staff had with the Commissioners was during their annual tour. Since the early 20th century the Commissioners made a series of trips around the state to inspect railways assets and operations. Known as the Commissioners' Special, the train would be made up of luxury carriages reserved for this purpose. The visit of the Commissioner was cause for as much trepidation as excitement, with staff and their families working hard to ensure nothing would displease the official eye.

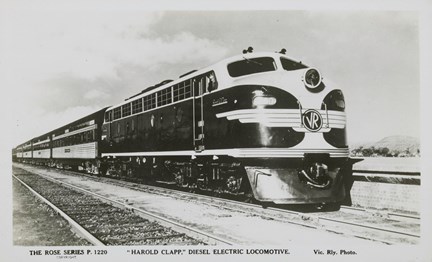

Commissioner Clapp

Social life

The railways are noted for their strong culture of friendship and loyalty amongst staff. Staff were encouraged to identify first and foremost as a railways employee and as a result they often formed strong social networks within the rail workforce.

Elements of the job encouraged a strong railways community. Shift work, irregular hours and frequent transfers to new locations impacted on the social connections made by railway workers. In some rural areas this was reinforced by the involvement of the entire family in the local operation of the railways.

Whilst many factors encouraged unity, the strict hierarchies and harsh discipline also created divisions. The codes of behaviour and details of uniform decoration that staff were required to adopt subtly communicated differences in status. Railway slang was one of the ways workers cemented their social connection, and expressed their disdain for the dry, officious language of the Department. The adoption of slang terms for elements of the railway system mirrored the development of a standardised official language for new technologies, systems and procedures, and expressed a pride in knowledge.

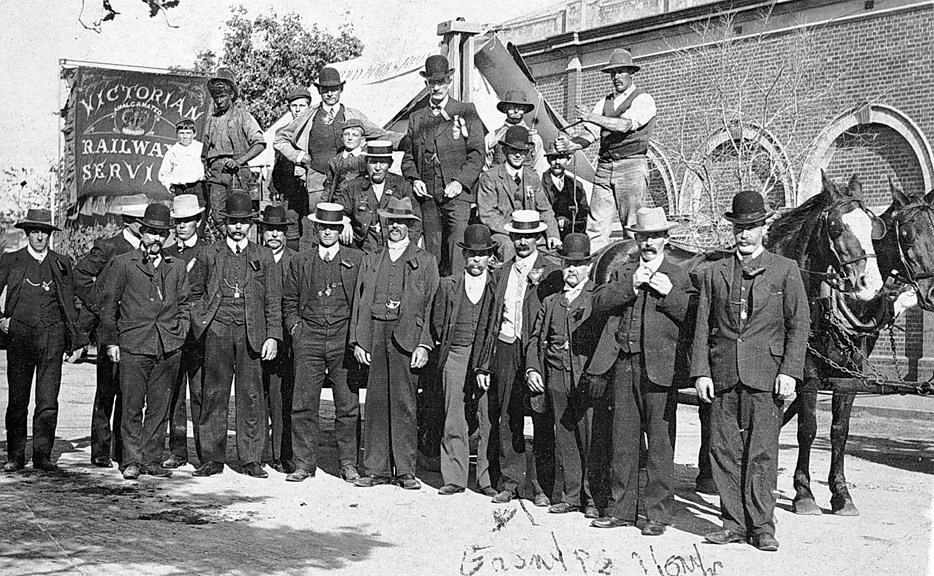

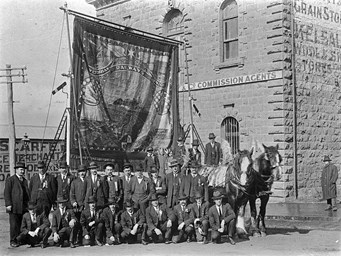

Unions played a significant role in creating the railways community through their advocacy work for employees and concern with improving the conditions for rail workers and their families. The educational and social activities of the Victorian Railway Institute also helped develop the railways community.

Exhibitions and street parades

Unions

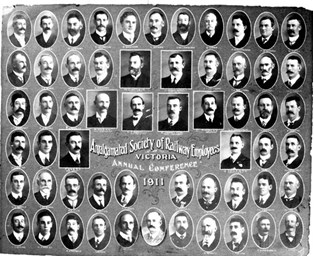

The majority of Australian railway staff are represented by a single national union, the Australian Railways Union (ARU). Established in 1920, the ARU was driven by a vision of a union which would address the concerns of all railway employees – an ambitious vision given the diversity of roles fulfilled by railway staff.

This aim had underpinned many of the early union organisations. These organisations operated in a hostile climate: in 1859 all government employees, railways staff included, were prohibited from belonging to political associations. When an organisation representing engine drivers and firemen attempted to affiliate with Melbourne Trades Hall in 1903 the government forbade this affiliation and, after three months of negotiation, engine drivers and firemen went on strike for seven days. From these actions emerged a recognition of the right of railway employees to be involved unions.

In 1911 several Victorian railways unions merged to from the Victorian Railways Union (VRU). In 1920 the VRU merged with interstate unions to form the ARU – a national union representing the concerns of Australian Railway workers. Several other railway-related unions continued to operate, including the Federated Engine Drivers and Firemens Association of Australasia (federally registered 1908-1949) and the Australian Federated Union of Locomotive Enginemen (1927-1993)

A significant period of industrial action occurred in the late 1940s and early 1950s, agitating for improved conditions and responding to Government erosion of existing conditions. These included a state-wide cessation of railway services for 55 days in 1950.

In 1993 the ARU merged with other union organisations to form the Australian Rail, Tram and Bus Industry Union.

Victorian Railways Institute

The Victorian Railway Institute (VRI) was an important focus of the educational and social activities for railways staff in the twentieth century. Based at Flinders Street Station, VRI was officially opened on 22 January, 1910. As the VRI grew 23 country centres were opened across rural Victoria. Its activities were largely funded by the Railways Department, who directed fines collected from employees towards its operation.

The VRI was central to the 'self-improvement' culture of the railways. Whilst education in railways-related skills was not mandatory, it was expected that staff would undertake training outside of working hours to maintain and develop their knowledge. Qualifications gave staff members a chance to climb the railways hierachy. Classes in bookkeeping, accounting and operation of new, railway-specific technologies were typical of the subjects workers were encouraged to complete.

Social activities were also an important part of the VRI. The central facility at Flinders Street featured a large lending library, billiard room, gymnasium and a concert hall which doubled as a ballroom. VRI offered activities as diverse as boxing, ballroom dancing, radio broadcasting and banjo classes, as well as running teams in a variety of sporting leagues. Employee-produced magazines were also published from the Institute.

Women of the rails

Women have filled a variety of roles within the rail service. Whilst some women were formally employed in roles including stationmistress, porter and upholsterers, many assisted their husband in his railways role without acknowledgement from the Department.

Significant numbers of women were first employed in 1920, when the establishment of the Refreshment Services Branch created roles for waitresses, barmaids, laundresses and cooks. By 1925 the Branch employed around 500 staff, predominately women. In the same year 326 women were employed by the Department as stationmasters and thirty as gatekeepers. From a pre-war level of around 800, female staff numbers rose to more than 1800 by 1943.

Whilst there has been some conservative resistance to the principle of employing women within the service, female railway workers have generally enjoyed the support of unions, the Department and the public. Reflecting larger social changes in the twentieth century, women were gradually accepted for employment in more diverse roles with the railways system. Despite this, women did not receive equal pay for equal work within the Department until the 1970s and female-dominated roles continued to be lower paid.